Co-production Rule #7

Expect the unexpected

The evening was a great success. You have a two dozen people signed up… curators, advisors, respondents, evangelists. They’ll start talking about this wonderful project and the wider community will start to buy-in to the notion of co-production.

You can now start calling people and setting up individual meetings. They know who you are now, and why you’re there. If you been curious, humble and human, people will be generous with their time and their histories. Informality is now the order of the day.

‘Hello, it’s Guy. We met the other night in the hall, and you said you might have some stories. I was wondering when would be a good time to have a chat…’

But before you lift that phone, think about the cadences, prosody and general tone of your voice. Be polite, charming and human. And be prepared to work evenings, weekends and holidays. The community have jobs and lives and family. They will fit you in when they can, which might not fit your usual working hours.

As for keeping track of who you’ve called and what you’ve said, a spreadsheet is a good idea, just to keep track of who you’ve arranged to meet and when. A diary is useful too, and when you’re there, Tweet or Instagram those photos, take those selfies, and remember to keep a note of those kilometres.

You’ll meet people in their homes, in fields, at heritage sites, in farmyards, at carparks, beside churches. You’ll drink a lot tea and eat a lot of cake (if you’re lucky) and you’ll lose hours just talking, or more importantly, listening. Photograph everything, record conversations if you want, with the respondent’s permission obviously. Document every second of the process. Enjoy every second of the process.

At the doorstep…

You’re meeting people in their homes. The door knocking etiquette applies as much now as before. How you dress, how you come across, what questions you ask, all of these are important too, and I’ll address them in more detail in On collecting histories, later on.

But while you are wherever you are, give yourself time to walk again. Soak up the atmosphere of the place. Take your camera, your audio recorder, for you never know what you might see or hear…

When you said unexpected, what did you mean?

It’s at this point in any community engagement, I always remind myself of this quote from the German military theorist, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder…

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

No, I’m not intimating for one second the community is your enemy, quite the opposite, but there is much truth in this infamous aphorism.

Co-production is challenging, ambiguous, unpredictable and scary. Outcomes and outputs will be discarded, unintended consequences will unfold, and previous evaluation methodologies will be utterly unsuited.

Those lines from earlier are worth repeating now. Whatever you had planned, whatever was said in your application about outputs, and whatever you thought was going to happen, all of that goes out of the window, the moment you start talking to the community. There is nothing quite so frightening and exhilarating as the sharp-end of community participatory engagement.

Here’s what will happen…

What you thought you knew was wrong

Your official version of history, distilled from all that desk-based research, will evaporate in the face of tales, local stories and real people.

“Did you know, the island’s original name in Irish was Inis na n-Osirí? The island of the oysters. I heard that, don’t know where.”

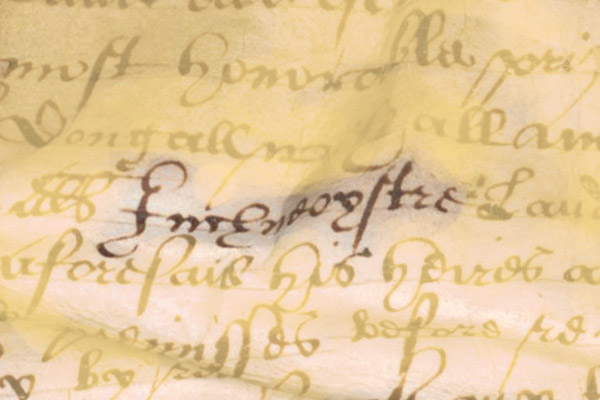

It took the discovery of a document from 1603, located in the National Archives in London, to verify that Inch was once Inchneoystre, Inis na n-Osirí.

Who you thought you should talk to were the wrong people

“Aye, I did sign up, but really you should be talking to Davy. He’s the fellah who knows about the…”

What you thought was important wasn’t

“Oh aye, the church is interesting enough, but did you know about the Flemings? Now there’s a story.”

What you thought was nothing was a lot of something

That wreck of a boat, nothing of interest there…

The photo above and below is of one of the Brown’s fishing boats, the Shenandoah, I think. But this one photo contains so much more history.

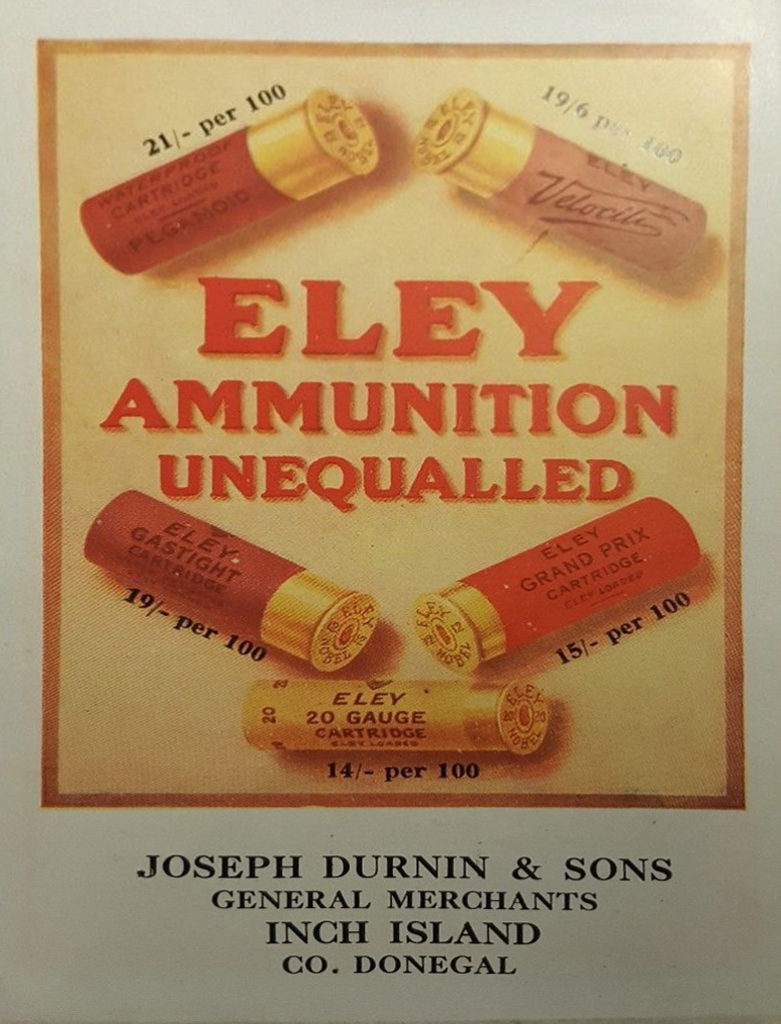

The buildings to the left of the boat were once owned by the Durnin family, whose shop on Inch sold everything and anything. They had three shops, one on Inch, one at Burt and the one in the photo. They were also island’s undertakers and ammunition dealers…

The sandbar to the left is where the mass rock once was, during the time of the Penal Laws, and as for the story of the Helicopter… that will have to wait for another day.

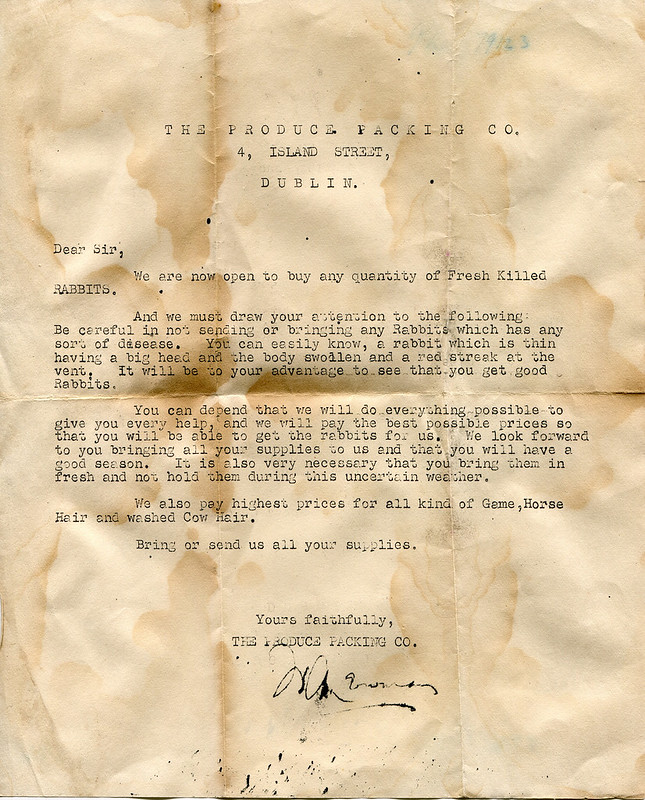

History will come out of the woodwork… and dusty drawers, attics, farmyards

“I have the old millstone. Nobody seemed to be that interested. And those bullauns? I built them into my garden walls. There’s one down by the road.”

Bullaun stones are stones containing one or more depressions made into the stone. The originated in the Neolithic period although most of the remains have been found in early monastic sites. They have a strong superstitious link and their original function is not clear. They were also known as ‘cursing stones’.

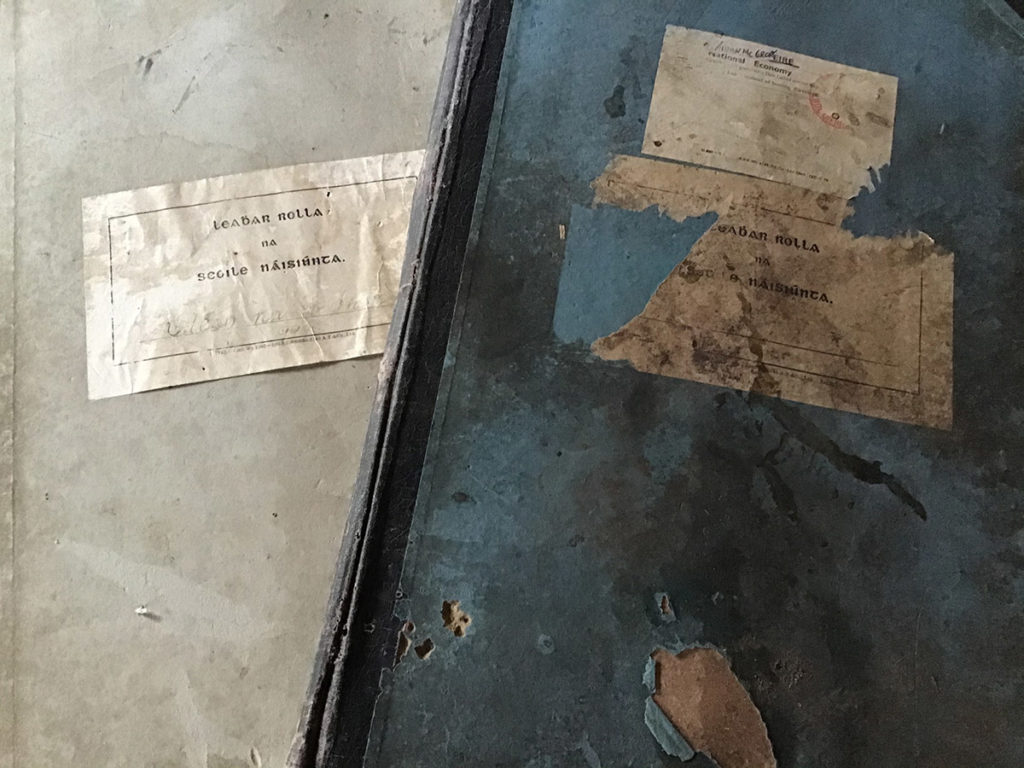

“I was working on the old school, and I was up in the attic and I found them lying there. Nobody else wanted them and I thought they might be worth keeping.”

Paddy McGrory, on finding the Inch School roll books from the 1940s

“Would that be of any interest?

And people will be so incredibly generous, you’ll feel almost embarrassed at times…

Perspectives IX

That picture of the keys to Inch Fort. You’ve seen it earlier. This is just one example of how generous and trusting people can be if you’ve done your co-production facilitator’s job well, and your gatekeepers and evangelists are onboard.

Patricia, Meitheal and the Fort

Inch Fort is owned by the Meitheal Trust. Meitheal was a spiritual community, set-up in the 1980s, that bought the fort from its previous owner. It’s no coincidence that this manual uses the same title.

Maria, the gatekeeper, passed on my number to Patricia, one of the trustees. Patricia called me and I explained the project to her. This was before the public meeting, as I knew the fort was likely to have a fascinating history. After chatting for ten minutes, she invited me to meet her at the fort in early January. I arrived at lunchtime, to soup and scones and the warmest welcome. I spent most of the afternoon with her, and Peace, the dog. Peace was my best friend after an hour… dog treats. Patricia had maps, plans, documents and a whole history of the fort, already researched.

We talked about the fort, about the Meitheal community, about her plans for the future, about angels and landscape acupuncture, about war and peace. We walked around the site, and I photographed everything. The history of the fort is a tale of geography, paranoia, rebellion, Imperial aggression, itinerant labour, arms-races, civil war, and more.

As I was leaving, I was hoping to organise another visit, to take further photos.

‘When would be a good day? I can come over any time really, whatever suits you.’

Her answer was to hand me the keys.

“Take those, then you can come and go anytime. And use the cottage if you want to stay over. Just let me know when you might be here”