Once upon a time, you learned how to speak Euro-ese. You filled out your funding application. You submitted the form and your supporting documents, and then you sat, furiously checking your emails for the next three months until you finally received a response, offering you a grant, with the usual ‘certain conditions’.

This email can often be found in the Spam folder, so it’s always worth checking there too. This isn’t a joke. This actually happened to me. I found it a week later.

You run around the room punching the air, because the Special Euro-Project Secretariat (SE-PS) has decided to give you several thousand shillings to work on a community co-production project, even though there is a distinct possibility that neither the SE-PS nor your management team know what this actually entails. You sign the documents, agree the conditions, and you are ready to go and co-produce… but with whom, where, and why?

You may have already identified your target community, and included the information in your funding application/workplan, but please keep reading, for there are a few things still to consider before you leave the office. And if you haven’t found your community, then the following suggestions may help you narrow the field.

Follow your heart. Be passionate.

Passion is an over-used term. I’ve even seen it applied to cardboard packaging, but there is little to be gained from community engagement if you aren’t interested in that community or can’t summon any enthusiasm for the project. The people you meet will feel it – the quality of the engagement will suffer, the information will dry up, and you’ll be miserable. Good co-production doesn’t necessarily have to be the most exciting and fun thing you’ve ever done, but you are the facilitator and primary contact between the community and your organisation – if you arrive with a long-face and try to feign interest, you won’t get very far.

Follow your interests. Use your expertise.

If you have a fascination for oral history, megaliths, or social and political changes in the 18th Century, use that knowledge to search for communities that lived through those histories. Find a connection you can follow through, and one which keeps you interested.

Think local.

Consider your travel time and your carbon footprint. If the community is two hours drive away, that’s half a day travelling to and from them. There might be good reasons to make the journey, and those reasons outweigh other considerations, but query your choice. Ensure you look at your resources, your patience, and how many times you can survive four hours behind a steering wheel.

As set out in the application…

Remind yourself of what you said you were going to do in that funding application, three months ago. It’s easy to forget, if like me, you are constantly filling out forms and sending them off. Balance the project’s aspirations with practical and real-world considerations. If you need to go back to the funders or your organisation’s management to notify them of variation, ensure you can make a good case.

Use your personal contacts.

Your friends and colleagues can be a mine of information. Ask questions. Tell people what you are hoping to do. Someone, somewhere might just have the connection you need.

Where on the map?

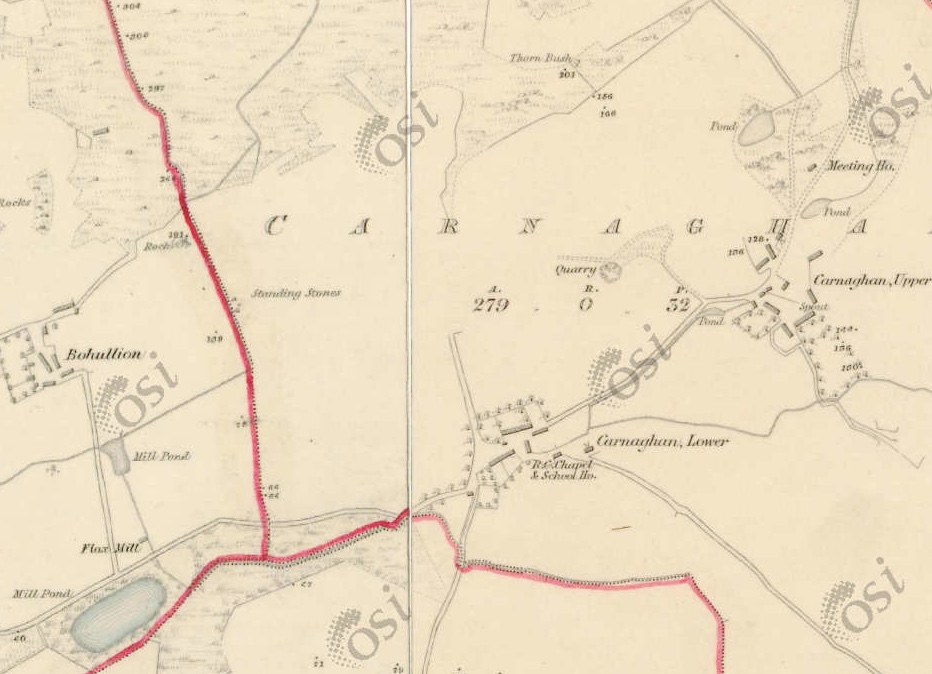

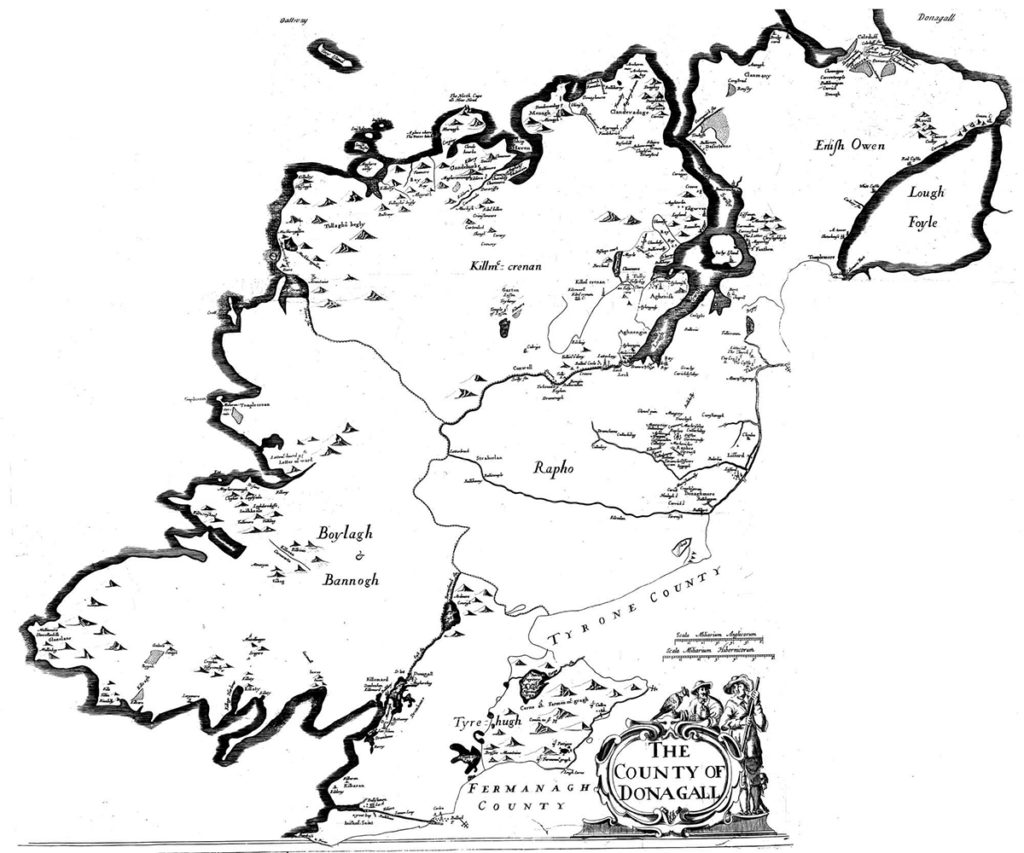

Get some maps, paper or online. We’re lucky to have a treasure trove of maps from the Ordnance Survey of Ireland. 6″ colour maps, as below, (1837-1842), made by British Army surveyors, and 25″ versions (1888-1913). They were some of the most accurate maps ever made with traditional surveying.

Look at the geography, look at the roads, look at those places you’ve never been to, or places you’ve heard about, but never taken too much interest in. Set yourself some parameters: Rural or Urban, Maritime or Agricultural, Geographically Isolated or High-Density. Think about socio-economic factors and cultural impacts, infrastructure, both traditional and digital. Make a list, then go back to the maps and circle some possible candidates. Have a look at the Why? page, to see how we chose Inch, or rather, how it chose us.

Go there.

Visit the place, before you’ve made any decisions. Talk to people, but be a little circumspect. Get a sense of the place and the community. If your co-production facilitator’s radar is switched on, you’ll know instantly if it’s the right place. And honestly, I can’t tell you what that means for you, but you will know – the community, the place, the location, all of it will just feel right.

Established or establish?

Weigh the pros and cons of working with an established group, or simply finding the right people. If you work in the museum sector and your focus is heritage, there might be an extant history group, already working on the community’s history. They may be the obvious choice, but you must consider whether you might end up walking paths already trodden. On the other hand, working with a disparate group of people has its downsides…

Perspectives I

… and a few words about the last paragraph. The social, economic and political histories at play in a community markedly affect how receptive and supportive that community will be towards the co-production. And when I say politics, I mean politics with a small ‘p’… who is not talking to who, who sold a field fifty years ago and still feels cheated, who borrowed a wheelbarrow and never returned it, and in Ireland, whose father may have fought on one side of the Civil War.

You will never meet everyone in the community, not everyone will engage with the project, and you will have to accept this fact.

The same is true when working with an existing heritage group. You will have to navigate the individual interests and personalities; some of the group may become evangelists for the project, but not everyone will be so welcoming, for you are both the professional and the outsider at once. In addition, demographics and convention within the group may combine to create an idea of local history, which may not be reflected in the wider community.

The enthusiastic voices of an existing group may muffle the quieter voices, and anybody working in the area of oral history will tell you those quiet voices are always the most interesting. If you hear ‘Oh, I’ve not much to tell,’ you can be sure they were probably in some special-forces unit in several wars, played at Carnegie Hall when they were 14, and lived in an Alaskan log cabin for twenty years…

How you navigate all of these obstacles is down to you, but follow your heart, you will be half-way there. And yes, it is difficult for anyone to justify their instincts and their gut, but in my experience, the best work has started from an unconscious response to a place or community. Don’t ignore that response. The unconscious mind has a way of guiding you to ideas and impulses you may never have considered, but which are created and nurtured from your life experience.

Be passionate.

And I should add, there will always be the dissenting voice, the ‘you didn’t ask me’ voice, the ‘I didn’t know anything about this’ voice. There will always be someone who, for whatever reason, feels they didn’t get the opportunity to contribute or feels that you somehow snubbed them. It’s just part of the tapestry of co-production…